And The Engaged Cities Awards Go To . . .

This article originally appeared in Fast Company.

Cities of Service recognizes Bologna, Italy; Santiago de Cali, Colombia; and Tulsa, Oklahoma, for civic innovation through citizen engagement.

By 2050, an estimated 60% of the world’s population will live in cities, adding some 2.5 billion people who will no doubt strain services, governments, and housing. To overcome such challenges, often with limited budgets and thin staff, these burgeoning metropolises will need to tap the best thinking from both city hall and their citizens.

Cities of Service, a New York City–based nonprofit, is dedicated to addressing the problems of tomorrow today by helping local governments and citizens work together better. Its new Engaged Cities Award highlights the best examples of such partnerships and recognizes some of the world’s most innovative initiatives involving citizens.

The three winners of the inaugural award, announced yesterday at the Engaged Cities Award Summit in New York, span the globe: Bologna, Italy, which developed citizen-led reclamation efforts; Colombia’s Santiago de Cali, which created a program to effectively promote trust and peace between neighbors; and Tulsa, Oklahoma, which has implemented data-driven, community-oriented policy making.

From distant points on the globe, they’re all models of creativity and effectiveness in motivating citizens to get involved.

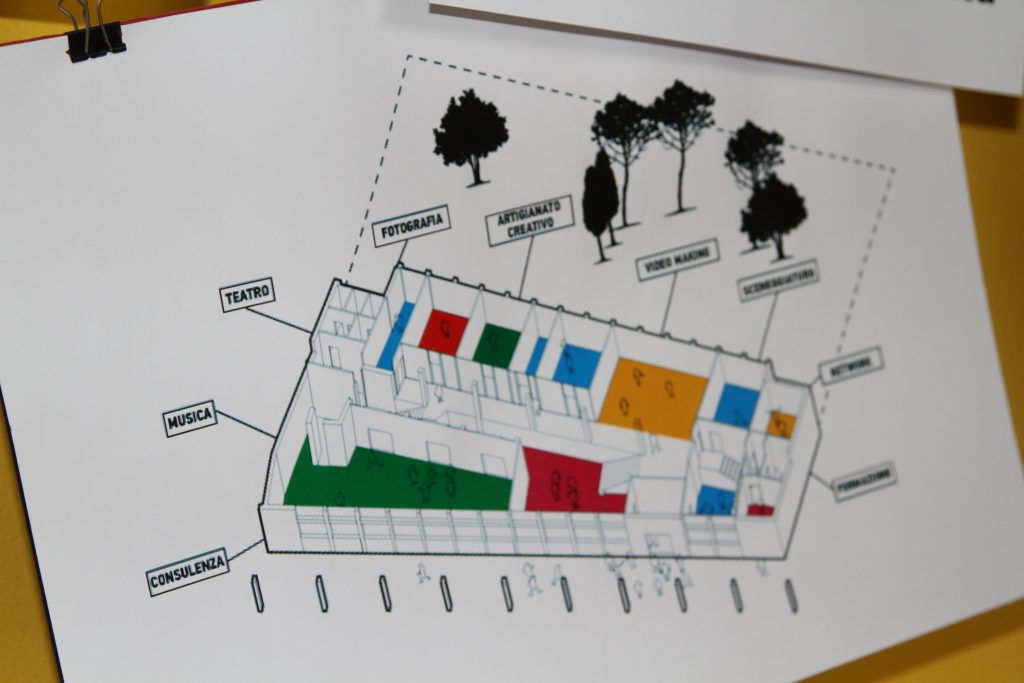

Plans to beautify Bologna

BOLOGNA: URBAN RENEWAL IN AN ANCIENT CITY

A few years back, some civic-minded citizens in Bologna decided to repaint a park bench in their neighborhood. They gathered the proper documents and outlined their plan—or, at least, as much of a plan as you need to paint a single bench. When they approached the city for permission, they experienced a whirlwind tour of local bureaucracy, from having to visit a half-dozen offices to endless paperwork and arcane rules about altering public property. News of their frustration traveled all the way to the mayor, who was disheartened—involved citizens couldn’t make even minor improvements to their neighborhoods because of red tape.

“The bureaucracy aspect was really, really tough to tackle,” says Matteo Lepore, Bologna’s deputy mayor for economic development. “So we decided to change the rules.”

Lepore and the rest of Bologna’s municipal government knew that the best ideas for civic innovation and improvement to public spaces were going to come directly from citizens who care most about and frequent these areas. “We knew that people were going to facilitate and conceptualize these commons projects,” he says.

With that in mind, the city adopted a new regulation allowing citizens to propose and implement improvements, eliminating layers of bureaucracy that had inhibited and discouraged previous efforts.

The change triggered a massive response: more than 400 “collaboration agreements” including community-based cleanup and beautification programs as well as entrepreneurial endeavors, reinvigorating huge swaths of the city. “After some years of participation in the districts, the people have more support,” Lepore says. “They’ve been involved in this grassroots democratic process and they’ve asked us to introduce new tools, new information, new technologies, and new data to be more at the forefront of innovation.”

The city has also introduced an “Office of Civic Imagination,” a new department focusing on giving citizens resources for these types of projects. Already it has spurred innovation hubs like Kilowatt, a social and environmental ideas incubator, coworking space, and community center in Bologna’s Giardini Margherita community. The brainchild of a citizens’ group, Kilowatt serves as both an ambitious effort to bring innovation to the 3,000-year-old city and a striking example of what’s possible when longtime barriers to new thinking are removed.

Technology plays a key role in Tulsa through a program called Urban Data Pioneers

TULSA: MAKING DATA-DRIVEN DECISIONS

Today, city halls collect more data than ever before, which prompts an uneasy question: What do you do with it? Some cities leave it on servers where it collects digital dust until the information is outdated and useless. Others, like Tulsa, Oklahoma, put their data to use and, with the help of a local tech community, create better informed programs that address civic needs with greater precision.

When G.T. Bynum was elected mayor of Tulsa, he knew city hall would be operating on a tight budget. “We did not have the internal financial resources to do everything that we saw could be done as far as analyzing data goes,” he says. “So, my chief of performance, strategy, and innovation had this great idea of creating a group that would allow anybody who works within the city—not just in his office, but any city employee—and also any citizen who would want to be a part of this group to pick projects they could focus on and utilize the data we have at our disposal to help understand issues and solve problems better.”

A new program, Urban Data Pioneers, has changed how Tulsa addresses everything from infrastructure upgrades to crime prevention. It has also altered the way citizens engage with their city by giving them a peek inside at the hard numbers and using them to help guide new initiatives.

Initially, one goal was addressing income disparity, the sort of complex issue that requires deep, data-based insight. “We had an Urban Data Pioneer team crunch a ton of data, and it showed us the greatest correlation to higher per capita income was educational attainment,” Bynum says. “High school graduation rate is very important and we’re working on that, but it’s only one step forward in a multistage process where we need to be fostering an environment where more people are getting advanced degrees in our city. When you hear it in retrospect, it all sounds obvious. But it wasn’t something that we had any data to back up.”

Today, Tulsa’s government is primed to make data-driven decision making routine, a strategic shift that makes for a more resilient city. They’ve already begun to use data to rethink how they evaluate street repairs and to investigate how they can use blight data to improve neighborhoods.

Citizens come together to help revitalize Cali, restoring trust within the community

SANTIAGO DE CALI: REBUILDING TRUST

Colombia’s Santiago de Cali is a case study in how to heal deep wounds.

In 2014, more than 200 people were killed in civil conflicts over bad business deals, overdue debts, small-scale drug trafficking, and other conflicts throughout the city. Often, they were killed by their neighbors. Mayor Maurice Armitage—who has been kidnapped himself on two separate occasions—knew firsthand that addressing such neighborhood-level violence could only be addressed with direct action. He created the Department of Peace and Civic Culture to provide institutional muscle to help solve the problem.

But citizens had grown weary and cynical. They didn’t trust city hall’s ability to reduce violence on its own. It wasn’t until Armitage’s team created neighborhood-level councils that meaningful change began. “The community was somewhat reluctant because of distrust of institutions,” says Carlos Libreros, the city’s secretary of peace and city culture. “We were able to overcome that suspicion thanks to the community initiatives that were part of the Mesas de Cultura Ciudadana para la Paz (Tables of Civic Culture and Peace). The communities wanted to set a shared vision and shared priorities to address complex problems that were identified by the community itself, and not as an action imposed by the mayor’s office.”

The grassroots campaign has paid off. The homicide rate has dropped dramatically—to the lowest level in 25 years—and communities all over the city are seeing benefits such as improved graduation rates, reduced drug abuse, and community space revitalization. More enterprising goals are on the horizon as well, with communities looking to build on previous projects.

“Communities are feeling empowered by the local councils,” Libreros says. “They’re getting increasingly ambitious in seeing the transformation of the city. The communities are advancing, and it’s feeding that mission-driven local energy and encouraging other citizens to join in.”

City leaders in Tulsa, Santiago de Cali, and Bologna are removing the barriers between local government and citizens, and in the process discovering what it means to be a truly engaged city. They’re experimenting and improving as they go. Their efforts not only improve a local community, but also inspire communities elsewhere. That engagement and that sense of progress ripple out, from city to city, citizen to citizen.