Your download is ready. Click here to download.

Since 2005, Fort Collins, Colorado, has used a budgeting process that bases budget allocations on the effectiveness of city programs. The process was initially disconnected from citizen involvement, so the city created an outreach program to inform residents about the budget and seek their input. Residents and community organizations were asked to complete a survey online and at events ranking their top priorities for the city. The survey also offered the option of going deeper and ranking all 500-plus budget proposals through a tool called Balancing Act. The increased outreach brought more citizens into the budget process and built relationships with organizations, schools, and nonprofits — relationships that have continued to grow since the program began.

The Problem

Fort Collins, Colorado, is no stranger to community engagement. Since 2005, the city has created its biennial budget using a process known as Budgeting For Outcomes, which bases budget allocations on the effectiveness of city programs. There’s a focus on accountability and innovation, and this has served the city well in managing its more than $600-million annual budget.

When Fort Collins started using Budgeting for Outcomes, the emphasis was on transparency, according to Ginny Sawyer, a project and policy manager with the city. It was in the midst of the recession, and the city was forced to lay off more than 100 people, so it wanted to be open about how and why the reductions were made. The Budgeting for Outcomes process made it easier for residents to see that their tax dollars were going directly to the services they used every day like roads, water, and public spaces.

City Manager Darin Atteberry, who was instrumental in implementing Budgeting for Outcomes in Fort Collins, says that they went from “whining for dollars to budgeting for outcomes. We were trying to move from a system that just funds city departments and teams to funding outcomes.”

Committed to continuous improvement, the city expanded and refined the processes it was using for Budgeting for Outcomes during each budget cycle. This included introducing a strategic plan to help guide the budget decisions. The strategic plan is a five-year road map that contains the city’s seven priorities, or “outcome areas”: neighborhood and social health, culture and recreation, economic health, environmental health, safe community, transportation, and high-performing government. Every odd year (the budget process occurs on even years), the city updates its strategic plan and conducts public engagement to review progress and make adjustments. This involves the Fort Collins Community Survey, a large, statistically rigorous survey sent out by the city to residents. The city also conducts special events to gather feedback from citizens.

All of this feedback is incorporated into the strategic plan and then into the budgeting process as well, providing the city with a deeper understanding of community priorities and helping to build trust between the city and its citizens.

Fort Collins’ citizens are highly educated and slightly younger than the average resident in the U.S. They also tend to be civically active and passionate about community affairs.

Atteberry strongly believes that collaborating with residents to is key to good governance. “Local government can be great,” he said. “I don’t think you can be great without having an incredible commitment to engagement.”

And while collecting and incorporating community feedback has always been part of the Budgeting for Outcomes process, the city wanted to take a more innovative approach, providing even greater transparency to residents and giving them more of a voice in terms of how their tax dollars were spent. In addition, the outreach for the strategic plan and Budgeting for Outcomes tended to rely on many of the same groups and people, not reflecting the diverse makeup of the city. The city wanted to change that.

The Solution

Fort Collins set out to systematize the process of citizen engagement and broaden who it was hearing from for the 2017–2018 budget. Annie Bierbower, the senior coordinator of public engagement, said that in recent years, the city had put a priority on public engagement overall. “That played a big role in putting more energy, not just into engaging people but doing it better–reaching more people, reaching different people,” she said.

Bierbower and David Young, a strategist on the city’s communications team, worked together to develop a new outreach strategy. They built upon existing outreach efforts to collect community input for the strategic plan and incorporated feedback from the Budgeting for Outcomes teams.

Nuts and Bolts: How It Works

Community Outreach

The overarching goal of the 2017 Budgeting for Outcomes process was to garner feedback from the community. To this end, Fort Collins developed a simple budget survey that residents and community groups could fill out to prioritize the issues that were most important to them. This survey included the strategic plan’s seven outcome areas with three to six themes associated with each. Themes included things like affordable housing, historic preservation, bus services, and water quality. Respondents were asked to rank the top three in each outcome area.

The survey was available online and at events and was printed in English and Spanish. This was the first time the city had prioritized bilingual outreach.

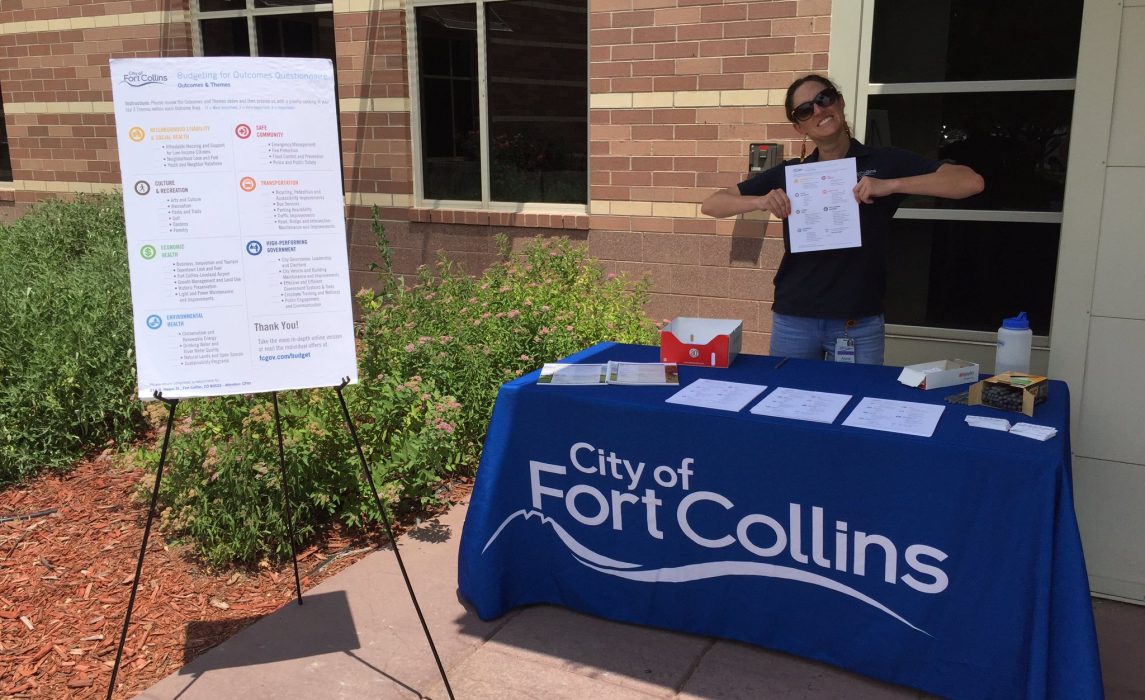

The in-person outreach occurred from May through August 2017 and included eight mobile budget booth events (one targeted to each outreach group) and 12 presentations to specific groups like Latino organizations, nonprofits, and housing and homelessness service providers.

The mobile budget booths were designed so that residents could get information about the budgeting process and ask questions of city staffers. The booths included printouts of the most recent budget, a copy of the strategic plan, large posters with the outcome areas printed on them, paper versions of the feedback activity, and tablets with which to complete the survey online. The city also gave out gold chocolate coins to help draw people to the table.

Bierbower and Young split up to host these events and involved fellow city staff. Budget Director Lawrence Pollack staffed several events, as did Communications Director Amanda King.

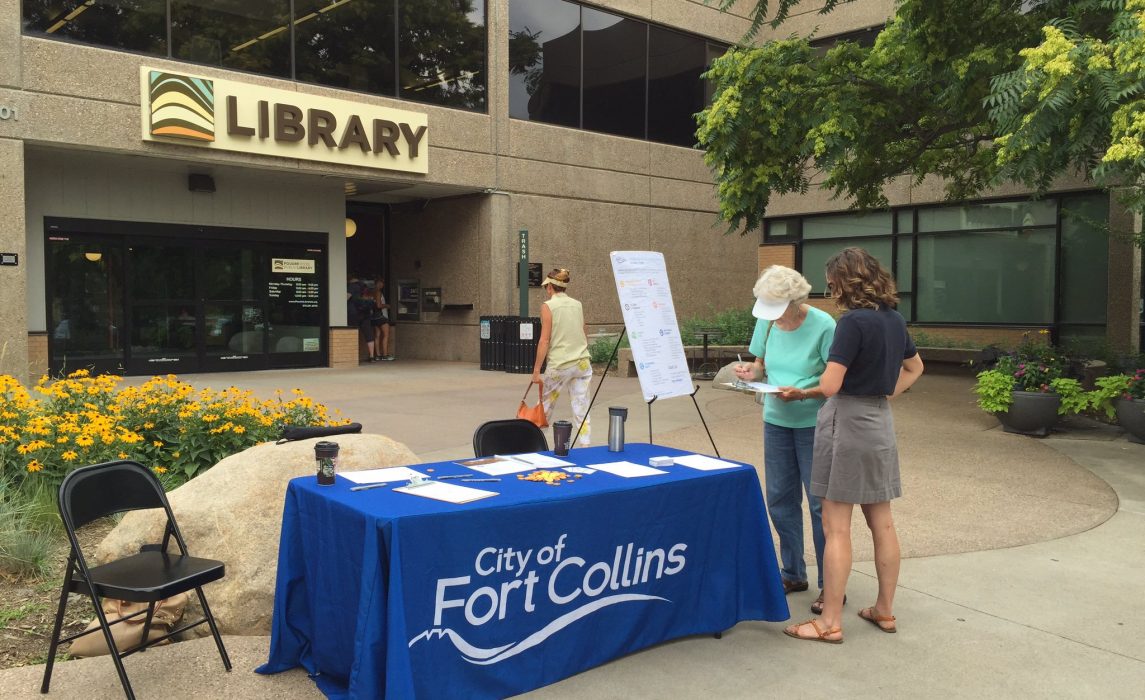

The booths were set up in high-traffic areas like transit centers, libraries, and farmers markets, with the goal of connecting with people who didn’t typically engage with local government. For instance, Bierbower said, at one library, the budget booth was scheduled for the same time as a children’s reading, since it was the library’s highest-attendance event and would give the parents time to participate.

“People could talk to us, ask their questions. They could take the survey home if they wanted to do more research,” Bierbower said. “We wanted to make it easy for people to engage however they wanted.”

For groups that wanted presentations, Bierbower and Young worked to tailor them to fit in with the existing structure and feeling of their meetings. For example, La Familia, an organization focused on the Latino community, held regular meetings that operated as open houses for families. They served food, entire families attended, and then people divided into small groups. Bierbower said the city had talked to La Familia leaders a number of times before the meeting. Because of that, the group’s leaders were able to facilitate the conversations in the small groups, describe the program, and answer questions in Spanish.

Community partners were key to broadening the city’s outreach and making sure a diverse set of perspectives were included in the budget process.

“Our nonprofits and community partners are our greatest asset because they have the trust of these populations that we’re trying to reach. They (also) have an existing platform, whether that’s a physical open house or an email list,” Bierbower said at the Engaged Cities Award Summit. “Working with those partners really builds trust and helps you reach a much more diverse audience.”

The increased budgeting outreach and the city’s work with community partners also extended to the next cycle of strategic plan outreach. Groups like the Chamber of Commerce, the food bank, Rocky Mountain High School, and Latino organizations receive regular communication from the city and work to incorporate Budgeting for Outcomes terms and information into their materials.

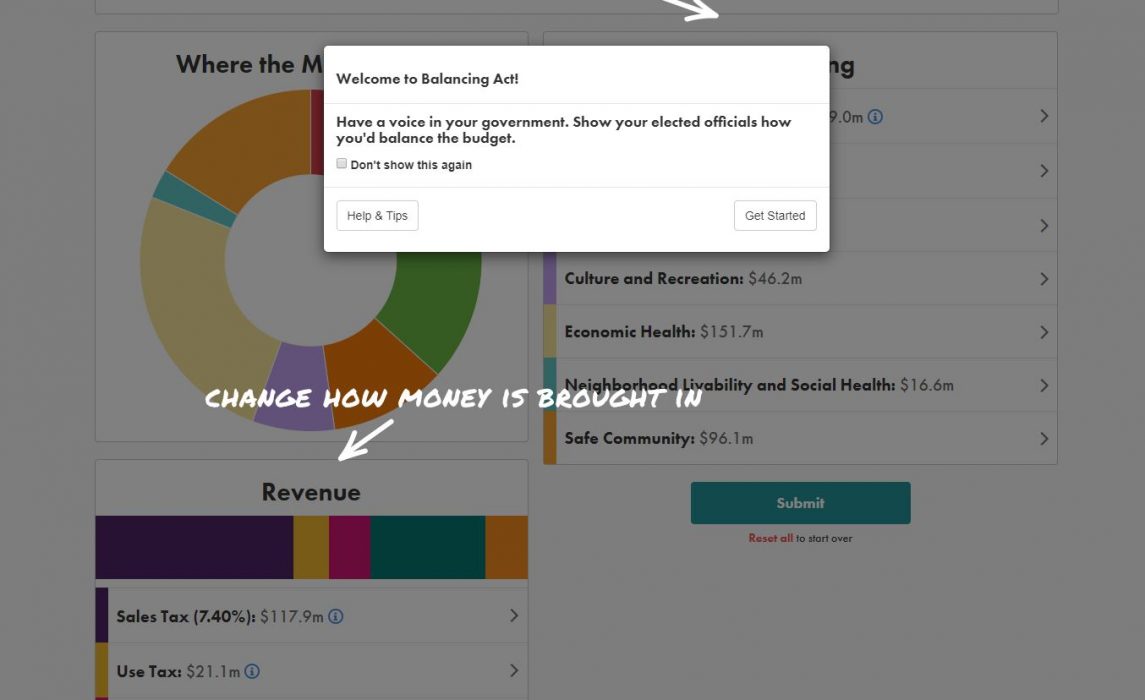

In addition to the booths and presentations, Fort Collins offered two online tools during the budgeting process, both of which were mobile-friendly. One was the survey, which asked people to choose three objectives in each of the outcome areas.

The second tool provided a much more in-depth look at the city’s budgeting process. Called Balancing Act, it allowed users to see how finances were allocated at a more granular level and to create their own version of the city budget. The interactive tool included all of the 500-plus budget proposals (called budget offers in the Budgeting for Outcomes process). Participants could go through it at a high level — reading through the outcome areas and allocating a percentage to each one — or they could look at each proposal and allocate individually. Colorful graphics showed whether the budget was out of balance. The exercise helped residents visualize the choices the city had to make to balance the budget and think about how they would prioritize the budget.

For those interested in delving more deeply into the budget, the city posted a document on its website that detailed all budget requests, both proposed and approved, so people could see exactly where their tax dollars would be spent.

Budgeting for Outcomes Teams

With each budget cycle that Fort Collins went through, it worked to increase citizen engagement in the process. One of the most significant ways the city did this was through its Budgeting for Outcomes teams. The seven teams (one for each outcome area) were set up when Budgeting for Outcomes launched in 2005. For the first couple of cycles, the teams were made up entirely of city staffers from various departments, but the city added one citizen to each team to increase citizen input and participation in the budget. A few years later, a second citizen was added to each team to further expand engagement with residents and ensure continuity on the teams.

Thus far, the citizens are chosen from those who already serve on city boards and commissions, alumni of a city civic education program, and existing volunteers. Sawyer said they look for a diversity of participants and ask people to commit for two cycles, which ensures that there is always one citizen member who has been through the process before. Each team is made up of seven to nine people and meets weekly from April through June.

The goal of the teams isn’t to do community outreach — it’s to read every budget request in their outcome area and prioritize them.

Rick Reider is a resident of Fort Collins who has served as a citizen member of the transportation team for the last eight years. Reider said the team starts by going through all the budget proposals submitted by city staff — an “exhaustive amount of well-written, well- supported” papers. He said the transportation team receives around 80 well-documented proposals each cycle. Teams evaluate and rank the proposals based on how they align with the strategic plan. As they start to whittle down the proposals, the team might ask the “sellers” (or the authors of a given proposal) to meet with them in person to provide more details or answer any questions.

Of the 80 or so budget proposals for transportation, Reider said about 20 ultimately get funded. The funding decisions are aided by what the city calls a “drilling platform.”

“Each team gets a budget allocation. Then they take the list that’s in priority order and fund until they run out of money,” Sawyer said. “There’s a line — the drilling platform — that shows what’s above the line and what’s below the line.” Everything above the line is funded. “It becomes a much more tangible process.”

This helps the teams visualize funding decisions, and it has also been used to show Fort Collins citizens how the budget process works. In the early years of Budgeting for Outcomes, the teams would host open houses, where they printed the drilling platforms and posted them on the walls and let citizens post stickers with what they wanted to move up or down. This approach also helps the city when it has to make budget adjustments down the road — officials can go back to the drilling platform to see what can be adjusted above and below the line to stay in budget.

The teams give both city staff and citizens the chance to deeply understand city programs and policies and the trade-offs that occur every time something is funded. The city staff on each team includes experts in the outcome area as well as those from departments that are not directly related to the outcome area.

“The last budget cycle, I was on the safety team, which I didn’t know much about at all,” Sawyer said. “I learned so much, and I’m sure that was true for half of that team.”

Not only does the team structure increase the knowledge base, it “builds advocates in the community,” according to Sawyer.

Reider agreed, saying that he often has conversations with people in the business community who question how money is being spent.

“I’m always first to say that I work with city staff and they fight tooth and nail to be very good at guarding the use of our funds,” he said. “It’s good for a citizen to be able to tell other citizens what a great job the city does with their tax dollars.”

Results

At the end of the 12 weeks of outreach in 2017, all of the community’s input (data, anecdotes, feedback exercises, the interactive budget tool, social media responses, etc.) was compiled into a report by Bierbower and Young and shared with city leadership, city council, and the public.

As they do every year, the Budgeting for Outcomes teams each compiled a report that ranked all the budget requests in their team’s focus area. Their recommendations went to the budget lead team, which compiled memos from all seven teams into one report that’s given to the city council.

The city received 284 completed surveys for the 2017– 2018 budget. Of those, 155 were submitted at on-the-ground events or via email and 129 were completed online. Bierbower said many of the surveys were completed by groups or organizations, so the total number received represented more than just 284 individuals. One example of this was the Vida Sana Coalition, which brought together a range of nonprofits and service organizations. Bierbower said the coalition held a meeting where the attendees broke into small groups that each focused on one outcome area. Each small group reviewed all the budget proposals within its outcome area and discussed priorities. Then the Vida Sana Coalition submitted a letter that listed all of the proposals that the group supported. “We helped those conversations happen, but they really took it and ran with it,” Bierbower said, adding that there were representatives from 25 to 30 organizations at that meeting.

After compiling all the results, the top five objectives across the outcome areas were:

- Improve access to a broad range of quality housing that is safe, accessible, and

- Improve the community’s sense of place with a high value on natural areas, culture, recreation, and park

- Improve community involvement, education, and regional partnership to make the community safer and

- Improve safety for all modes of travel including vehicular, pedestrian, and

- Improve traffic flow to benefit both individuals and the business

The survey also allowed for open comments, and 95 percent of respondents took the opportunity to include more detailed feedback. Bierbower and Young read through all of these comments and organized them into 14 different themes, the top four of which were affordable housing, multimodal and public transit development, controlled and planned growth, and environmental sustainability.

All of the responses fed directly into the budget process. The outreach information was compiled into a summary report that drove part of the discussion creating the city manager’s recommended budget. It was also given to the city council for their work on the budget.

One of the most requested projects was an expansion of the public transportation system to include Sundays and holidays. This had been asked for in the past by residents at city council meetings and other venues, but sufficient funding was not available.

“The reason they were so successful is the community took (the issue) on as their own,” Bierbower said. “With the extra outreach and extra materials, people were able to organize themselves around it. It was easy to see all the groups asking for the same thing.”

That included advocates for disabled residents and low-income residents, who said additional bus service, especially on Sundays, was needed for residents to reach jobs and to live independently. It was also supported by groups promoting multimodal transportation and transportation equity, as well as by residents who were concerned about congestion in Fort Collins. Bierbower said people attended city council meetings, organizations wrote memos, and groups filled out the survey together.

City council member Kristin Stephens recalled disabled rights advocates telling her, “We don’t disappear on Sundays. We just stay home.”

The 365 Transfort program, which added $375,000 a year to the city budget, had community buy-in in other ways: The city council reached out to Colorado State University to help fund the service, which provided half of the additional money needed. The student body, Associated Students of Colorado State University, voted to fund the remainder with student fees. Both organizations signed on to provide additional funding through 2018.

“This broader (outreach) strategy included organizations and groups that have felt disenfranchised or unheard in previous initiatives,” Bierbower said in her initial Engaged Cities Award application. “There were feelings that even though input was gathered, it would not truly be included in the decision-making process or necessarily even reported accurately. This is one of the many reasons why the 365 Transfort Service and increase in the Human Services dollars were imperative to success of this outreach and the next. The community could see a clear win.”

Stephens has also noted increased participation from nonprofit groups. “One of the good things about bringing people into the budgeting process is they actually see the cost of some of the big capital projects,” she said. Before, they didn’t have a concept of what some of those costs are. “It’s good for them to know and then they can help us make good decisions.”

Keys to Success

By providing different avenues for engagement that allowed residents to delve deeply into the process or quickly provide feedback, Fort Collins was able to reach more citizens and a broader range of community members.

“There’s a need for all different levels of engagement,” Bierbower said. “Some people want to read all 500-plus (proposals) and some people just want to (vote for) the thing they like.”

When Bierbower and other members of her team started the outreach for the 2019 – 2020 budget cycle, “it was so much more familiar to people,” she said.

But even so, city staff have continued to improve their engagement efforts. They realized they needed to do more to educate residents. Part of this was redesigning the city’s budget webpage to make it more user friendly. They made the outcome areas clearer and focused on how they connected to the overarching strategic plan, showing how budget requests were built directly off the objectives.

They also rethought how they were using Balancing Act, which cost about $1,300 a year for the 2017 – 2018 budget cycle. (It has increased in subsequent years as the tool was improved.) Ultimately, 96 people went through the in-depth process on Balancing Act, which Bierbower acknowledged was not as many as they had hoped.

“We heard some mixed feedback — some people loved it and some thought it was too difficult,” she said. “We decided it could be better used as an educational tool.”

Even so, 1,880 users spent an average of more than nine minutes on the site.

“The time that they spent on the page led us to believe that people were reading some of the things and learning some of the information,” Bierbower said. “Even though the number is small percentagewise, the quality is really good.”

Bierbower said one thing people struggled with during the first cycle was a lack of context around the spending. “We might say culture and recreation spends however many millions of dollars, but they had no way to know if that was expensive, cheap, or how it compared,” she said. So during the most recent budget cycle, the city included current spending levels as part of the feedback form.

These changes were largely due to the open comment portion of the feedback form, which gave residents and organizations a chance to weigh in on everything from lack of clarity to language choice. As a result, open comment options were added to other city outreach programs as well.

On a structural level, Bierbower said the outreach process was time intensive — at the height of the program, for about six weeks, it took up at least 40 percent of her time. There were a number of in-person events, and city staff was in the community presenting to organizations, answering questions, and working in the mobile budget booths. Because of this, communications staff involved in these events, who otherwise had little exposure to the inner workings of the city budget, needed to be more deeply briefed on the issues. Communication staff members now serve in other roles in the budget process, like the Budgeting for Outcomes teams, as well as in outreach and content creation, so they are better acquainted with the budgeting process.

The additional time and effort that the city put into the budgeting process proved effective. One of the primary goals of the expanded outreach was to hear from more people and include a more diverse array of perspectives when creating the city’s budget. The 2017 – 2018 survey saw a nearly 5percent increase in Latino respondents. Bierbower acknowledged it was a small amount — “we’re still just getting started” — but said in previous years there weren’t any native Spanish speakers involved in the Budgeting for Outcomes process, so she was happy that it was bringing more people in.

Bierbower said she feels that they met the goals she set out at the beginning to reach diverse communities.

“We wanted to catch people who don’t typically talk to government, be in new places, see new faces, have new faces see us,” she said. “That’s where the mobile budget booths came in — we got to talk to a lot of people who had never heard of the [Budgeting for Outcomes] process before, and that was our goal.”