Building on a Foundation of Digital Inclusion

Lessons about Virtual Engagement from Aarhus, Denmark

When cities implemented social distancing measures to stop the spread of COVID-19, local officials around the world experimented with virtual engagement to reach residents and gather input. But with a gaping digital divide in many communities, doing so effectively isn’t easy.

Aarhus, a municipality in Denmark of more than 300,000 residents, found success by building on a foundation of digital inclusion.

Aarhus has a history of experimenting to increase participation in government. In 2014, city leaders created the Digital Neighborhood, placing installations resembling old-fashioned phone booths across the city where residents could record answers to questions about participatory budgeting and city planning.

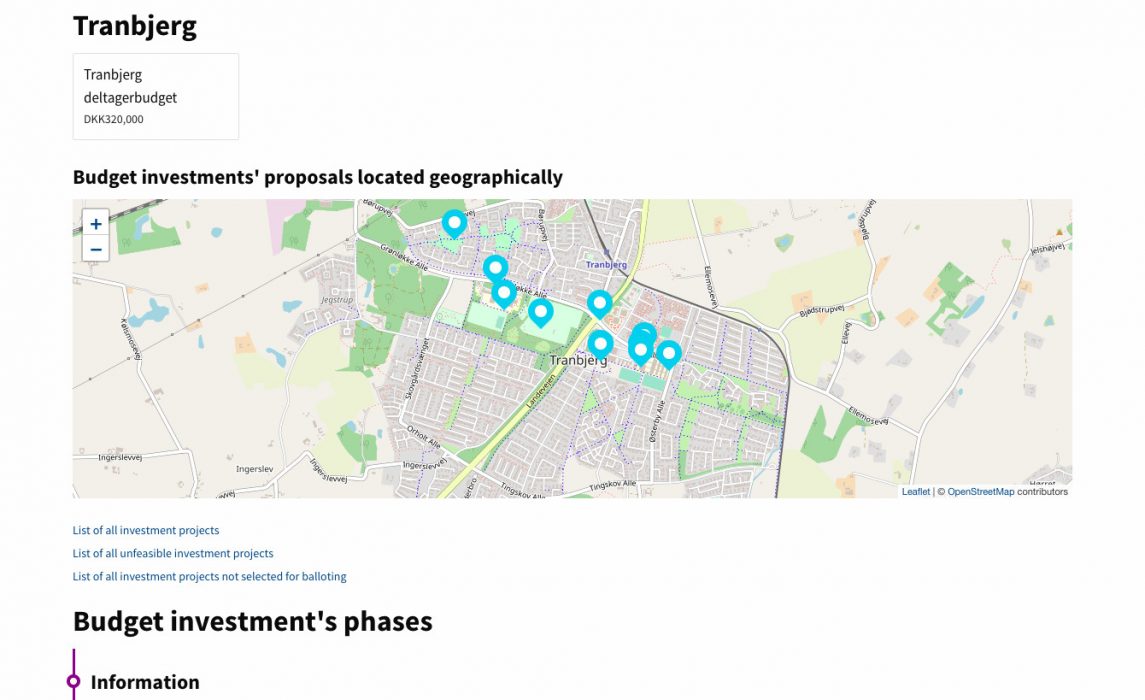

More recently, Aarhus used Consul, a free, open-source platform pioneered by the City of Madrid, to host a participatory budgeting initiative. The initiative took place in the suburb of Tranbjerg, which is part of the Aarhus municipality.

“What we are interested in is how we can use these different kinds of digital tools to strengthen the relationship and participatory democracy,” said Frederik Ingvardt Pedersen, a development consultant for Aarhus.

It’s essential to use well-tested technology, city staff said. It is also important to keep participation simple and with a low barrier entry. Participation should not be complicated by demanding a lot of reading or too many criteria for eligibility.

It’s essential to use well-tested technology and keep participation simple with a low barrier to entry.

Aarhus designed its Participatory Budgeting Process to meet these requirements.

The city set aside 320,000 Krone (about $51,000) to be spent on projects proposed by residents. Fourteen projects were submitted and about 16% of the Tranbjerg population over 15 years old voted, a good turnout for this kind of initiative according to city staff. While the minimum voting age is 18 in Denmark, the city opened up the participatory budgeting to those 15 and older in order to engage young people in democracy at an early age.

“In elections and citizen participation, young people are an underrepresented group,” said Pedersen, “so this is one of the groups we try to reach through our platform. We believe democratic participation is a habit that should be formed at a young age.”

It is important that cities delegate actual power to citizens and make sure their input is used in formal decision making about issues that are important to them, added Pedersen.

This empowers residents and encourages participation.

Aarhus residents voted on the proposals and selected six projects to move forward. These projects will create outdoor facilities for all ages, such as new playgrounds and walking trails. Residents are developing and implementing the projects with technical assistance and funding from the city government.

A Digital Mailbox for Everyone

One reason for the success of participatory budgeting in Aarhus was the existing infrastructure the city and the country has built over time. Everyone in Denmark has a government-issued digital mailbox where they can receive email from government authorities. The government has spent time and resources training residents to use the mailbox over years, including a national campaign and local programs, typically run by libraries and NGOs, to help elderly people gain digital competency.

Aarhus staff used this platform to their advantage, contacting residents about the initiative via their mailbox.

Most communications residents receive are one-way messages from local, regional, and national governments. City staff were a little concerned that their messages would be ignored or come across as spam. To counter this they changed the tone. Residents are usually addressed as taxpayers or reminded of their duty as citizens, so instead they emphasized the knowledge of residents and the power to make a difference by voting.

They received positive feedback. Residents were happy to learn about the opportunity to engage with their community, especially during the pandemic.

Community Members Spread the Word

The city also successfully used Consul to get resident feedback about Aarhus’s 10-year investment plan.

The mayor’s office had in-person events planned to gather feedback and prioritize spending for the plan, but the pandemic required them to quickly switch to virtual engagement.

Community members played an important role in advertising the initiative. The city reached out to those who had engaged with city government before, and held a workshop to educate them about the process so they could participate and help spread the word. The platform also has a function that allows users to easily share proposals on Facebook, so outreach happened organically as participants shared information with their neighbors.

Although the city only had about a week, they received feedback from nearly 4,000 residents, who submitted 72 proposals and many comments. Through the feedback they received, the city learned that many residents wanted to invest in a greener city with better infrastructure for biking and walking, as well as buildings that could host local sports and cultural events.

Building on a Strong Foundation

Many cities regularly rely on existing relationships with neighborhood groups to help reach more residents. These groups typically connected at in-person meetings before the pandemic, and members still have uneven access to technology. Cities and partners have had to step in and remove barriers to digital access and at times teach residents how to use electronic media to stay in touch.

South Bend, Indiana, for example, used funds from the Cities of Service Love Your Block program to award neighborhood groups and associations with free subscriptions to virtual meeting platforms, such as Zoom, and provide training to help members use the platforms.

Staying in touch with these community leaders can be done online as well. In Lancaster, Pennsylvania,Cities of Service AmeriCorps VISTA members joined the Neighborhood Group Leader’s Meetings, regularly occurring meetings with a city-wide cohort of neighborhood group leaders, which moved online during the pandemic. At these meetings, they shared information about city outreach efforts, new projects, and available resources.

These community leaders can then share information form the city with their neighbors, reaching a much larger number of people than city officials would by using their direct connections.

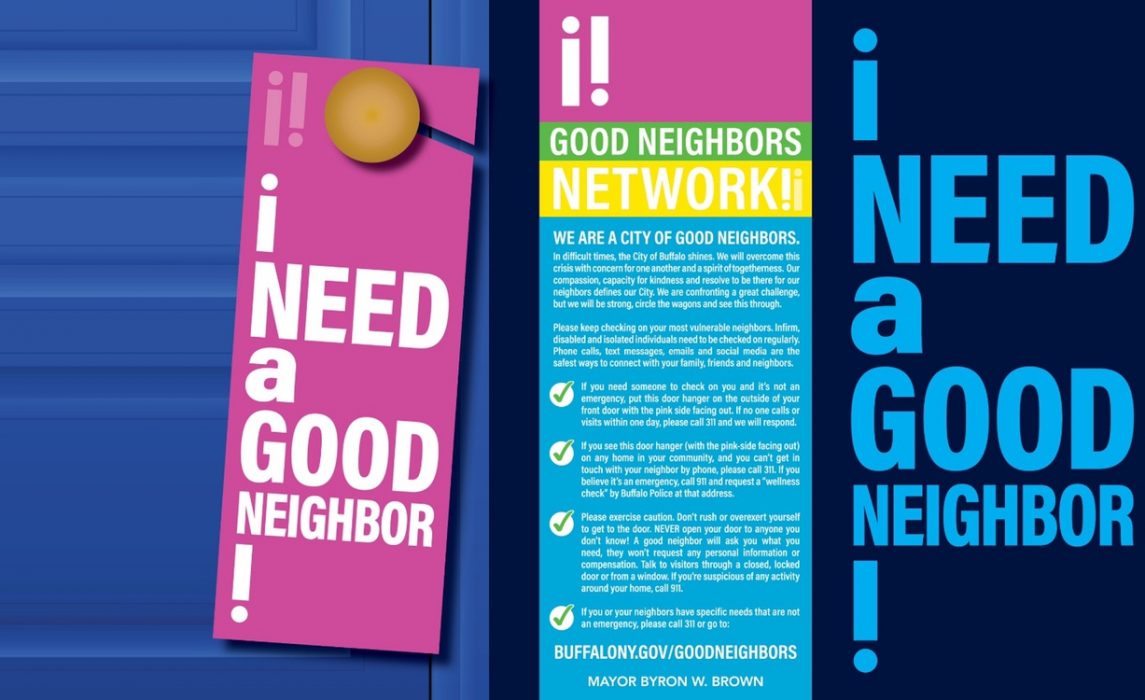

These efforts can be supplemented by door hangers with information from the city, like those used in Buffalo, New York. These door hangers were designed with colorful graphics to distinguish them for violation notices. Especially in cities with a large digital divide, taking these extra steps is necessary to reach residents who may not already be connected to the city.

Effective virtual engagement requires both good relationships with residents, as well as communities that have the technology and knowledge to participate online. Cities like Aarhus are demonstrating that once that groundwork is done, virtual engagement can go a long way toward bringing resident voices into decision making, even when city hall is closed to visitors.

If you would like to learn more from Aarhus city staff about their experience, contact Federik Ingvardt Pedersen at [email protected].